Reflecting on COP28 — and humanity’s progress toward meeting global climate goals

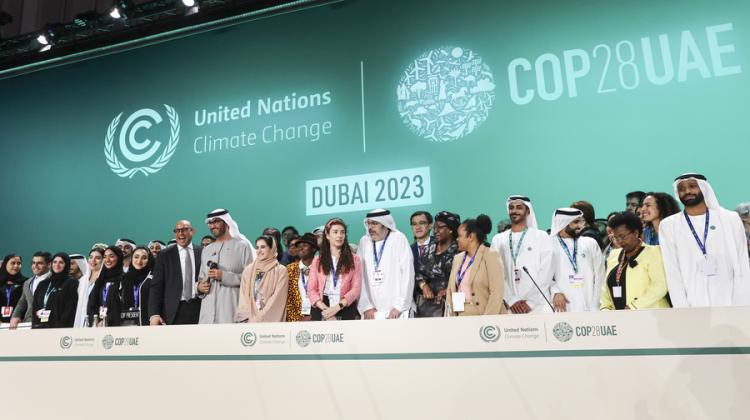

The closing plenary at COP28 took place at Expo City Dubai on Dec. 13, 2023. Photo: Mahmoud Khaled/COP28

MIT delegates share observations and insights from the largest-ever UN climate conference.

Office of the Vice President for Research

With 85,000 delegates, the 2023 United Nations climate change conference, known as COP28, was the largest U.N. climate conference in history. It was held at the end of the hottest year in recorded history. And after 12 days of negotiations, from Nov. 30 to Dec. 12, it produced a decision that included, for the first time, language calling for “transitioning away from fossil fuels,” though it stopped short of calling for their complete phase-out.

U.N. Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell said the outcome in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, COP28’s host city, signaled “the beginning of the end” of the fossil fuel era.

COP stands for “conference of the parties” to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, held this year for the 28th time. Through the negotiations — and the immense conference and expo that takes place alongside them — a delegation of faculty, students, and staff from MIT was in Dubai to observe the negotiations, present new climate technologies, speak on panels, network, and conduct research.

On Jan. 17, the MIT Center for International Studies (CIS) hosted a panel discussion with MIT delegates who shared their reflections on the experience. Asking what’s going on at COP is “like saying, ‘What’s going on in the city of Boston today?’” quipped Evan Lieberman, the Total Professor of Political Science and Contemporary Africa, director of CIS, and faculty director of MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI). “The value added that all of us can provide for the MIT community is [to share] what we saw firsthand and how we experienced it.”

Phase-out, phase down, transition away?

In the first week of COP28, over 100 countries issued a joint statement that included a call for “the global phase out of unabated fossil fuels.” The question of whether the COP28 decision — dubbed the “UAE Consensus” — would include this phase-out language animated much of the discussion in the days and weeks leading up to COP28.

Ultimately, the decision called for “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner.” It also called for “accelerating efforts towards the phase down of unabated coal power,” referring to the combustion of coal without efforts to capture and store its emissions.

In Dubai to observe the negotiations, graduate student Alessandra Fabbri said she was “confronted” by the degree to which semantic differences could impose significant ramifications — for example, when negotiators referred to a “just transition,” or to “developed vs. developing nations” — particularly where evolution in recent scholarship has produced more nuanced understandings of the terms.

COP28 also marked the conclusion of the first global stocktake, a core component of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The effort every five years to assess the world’s progress in responding to climate change is intended as a basis for encouraging countries to strengthen their climate goals over time, a process often referred to as the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism.”

The technical report of the first global stocktake, published in September 2023, found that while the world has taken actions that have reduced forecasts of future warming, they are not sufficient to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global average temperature increase to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius, while pursuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

“Despite minor, punctual advancements in climate action, parties are far from being on track to meet the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement,” said Fabbri, a graduate student in the School of Architecture and Planning and a fellow in MIT's Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism. Citing a number of persistent challenges, including some parties’ fears that rapid economic transition may create or exacerbate vulnerabilities, she added, “There is a noted lack of accountability among certain countries in adhering to their commitments and responsibilities under international climate agreements.”

Climate and trade

COP28 was the first climate summit to formally acknowledge the importance of international trade by featuring an official “Trade Day” on Dec. 4. Internationally traded goods account for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, raising complex questions of accountability and concerns about offshoring of industrial manufacturing, a phenomenon known as “emissions leakage.” Addressing the nexus of climate and trade is therefore considered essential for successful decarbonization, and a growing number of countries are leveraging trade policies — such as carbon fees applied to imported goods — to secure climate benefits.

Members of the MIT delegation participated in several related activities, sharing research and informing decision-makers. Catherine Wolfram, professor of applied economics in the MIT Sloan School of Management, and Michael Mehling, deputy director of the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research (CEEPR), presented options for international cooperation on such trade policies at side events, including ones hosted by the World Trade Organization and European Parliament.

“While COPs are often criticized for highlighting statements that don’t have any bite, they are also tremendous opportunities to get people from around the world who care about climate and think deeply about these issues in one place,” said Wolfram.

Climate and health

For the first time in the conference’s nearly 30-year history, COP28 included a thematic “Health Day” that featured talks on the relationship between climate and health. Researchers from MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) have been testing policy solutions in this area for years through research funds such as the King Climate Action Initiative (K-CAI).

“An important but often-neglected area where climate action can lead to improved health is combating air pollution,” said Andre Zollinger, K-CAI’s senior policy manager. “COP28's announcement on reducing methane leaks is an important step because action in this area could translate to relatively quick, cost-effective ways to curb climate change while improving air quality, especially for people living near these industrial sites.” K-CAI has an ongoing project in Colorado investigating the use of machine learning to predict leaks and improve the framework for regulating industrial methane emissions, Zollinger noted.

This was J-PAL’s third time at COP, which Zollinger said typically presented an opportunity for researchers to share new findings and analysis with government partners, nongovernmental organizations, and companies. This year, he said, “We have [also] been working with negotiators in the [Middle East and North Africa] region in the months preceding COP to plug them into the latest evidence on water conservation, on energy access, on different challenging areas of adaptation that could be useful for them during the conference.”

Sharing knowledge, learning from others

MIT student Runako Gentles described COP28 as a “springboard” to greater impact. A senior from Jamaica studying civil and environmental engineering, Gentles said it was exciting to introduce himself as an MIT undergraduate to U.N. employees and Jamaican delegates in Dubai. “There’s a lot of talk on mitigation and cutting carbon emissions, but there needs to be much more going into climate adaptation, especially for small-island developing states like those in the Caribbean,” he said. “One of the things I can do, while I still try to finish my degree, is communicate — get the story out there to raise awareness.”

At an official side event at COP28 hosted by MIT, Pennsylvania State University, and the American Geophysical Union, Maria T. Zuber, MIT’s vice president for research, stressed the importance of opportunities to share knowledge and learn from people around the world.

“The reason this two-way learning is so important for us is simple: The ideas we come up with in a university setting, whether they’re technological or policy or any other kind of innovations — they only matter in the practical world if they can be put to good use and scaled up,” said Zuber. “And the only way we can know that our work has practical relevance for addressing climate is by working hand-in-hand with communities, industries, governments, and others.”

Marcela Angel, research program director at the Environmental Solutions Initiative, and Sergey Paltsev, deputy director of MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, also spoke at the event, which was moderated by Bethany Patten, director of policy and engagement for sustainability at the MIT Sloan School of Management.